Russian hybrid operations in Eastern and Southeastern Europe have entered a more aggressive phase, targeting states that are at different stages of European and Euro-Atlantic integration. Today, Moldova is the primary target of such pressure. Through the combined use of hybrid attacks, Moscow wants to slow down the country’s European trajectory and create space for a long-term political blockade. At the same time, recent arrests in Serbia, linked to networks of Russian loyalists, point to a regional logistical environment in which intelligence, criminal, and propaganda infrastructures converge. From this environment, resources, personnel, and narratives are distributed toward sensitive points across the neighbourhood.

Russian hybrid activities in Moldova ahead of the September 2025 elections are methodologically identical to those carried out in Montenegro in 2016. Moldovan authorities uncovered a Russian plot to destabilize the state during the parliamentary elections on 28 September 2025. On 22 September 2025 (one week before the vote), the Moldovan police, acting jointly with the Intelligence and Security Service (SIS), conducted a large-scale operation involving around 250 searches at more than 100 locations, including four prisons. The operation resulted in 74 arrests, mostly individuals trained in Serbia, on charges of preparing mass unrest and coordinating operations from Russia through criminal structures. Authorities seized weapons, ammunition, training equipment, batons, handcuffs, passports, cash, and other evidence of travel and financial transactions. Serbian authorities confiscated laptops, mobile phones, and radio-frequency detection systems from the organizers. The primary objective of the Russian para-intelligence operation was to incite disorder and civil unrest in the event of a victory by the pro-European majority.

Serbia served as the key hub for destabilizing Moldova. According to investigative findings, Russian security services established a training camp near Loznica (Serbia), presenting it as a religious pilgrimage site to mask the arrival of Moldovan and Romanian nationals. Instructors, Russians and Belarusians linked to the GRU, rotated through Serbia every 30 days, teaching tactics for orchestrating street unrest, breaking police cordons, and using weapons. Local organizers Lazar Popović and Sava Stevanović, former advisors to Serbian minister Nenad Popović, provided logistical support.

The tactics involving violent protests and special equipment mirror those described in the indictment of Montenegro’s Special State Prosecutor in the 2016 coup attempt case. In Moldova in 2025, as in Montenegro in 2016, GRU operatives were active with the same objective: destabilizing the state by provoking unrest, financing criminal networks, and organizing violent demonstrations. In both cases, Serbia functioned as the central hub for GRU’s para-intelligence activities. Evidence from the planned illegal activities in Montenegro included photographs, videos, uniforms, direct confessions, and €125,000 in seized cash, all confirmed by Serbian investigative authorities.

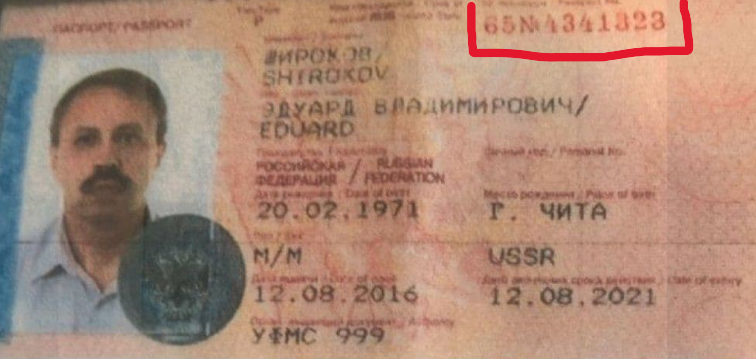

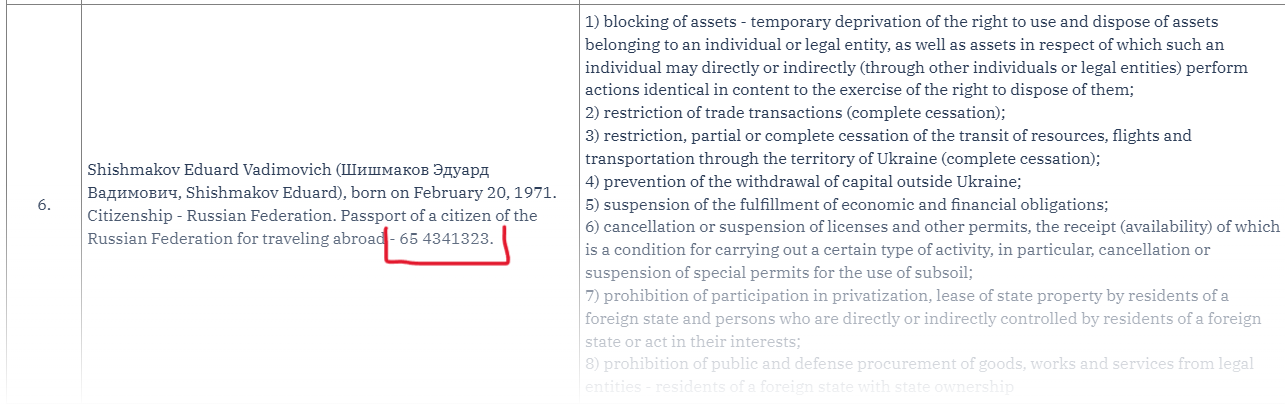

Photos 3 and 4: Passport of Eduard Shishmakov and the official announcement of sanctions imposed on Shishmakov by the Ukrainian authorities.

Regardless of the judicial outcome of the 2016 case, the facts clearly demonstrate that Russia applied an identical operational matrix in Moldova. The common denominator is not only the tactical behaviour of field operatives but also the integration phase in which both states found themselves. In 2016, Montenegro was on the threshold of NATO membership. Moldova’s 2025 elections were decisive for the country’s future EU integration. Propaganda outlets from the region and from Montenegro routinely downplay the significance of Russian operations to relativize the malign nature of its influence.

Further confirmation of the continuity of GRU activities across Europe is the case of Eduard Shishmakov, one of the individuals indicted in the 2016 Montenegro coup attempt. In 2024, he was included in a package of sanctions imposed by the Ukrainian government. The sanctions targeted individuals and entities from the Russian Federation working against Ukraine’s independence and territorial integrity. Notably, the passport number under which Shishmakov was sanctioned matches the number of the forged passport issued under the name Eduard Shirokov, which he used when entering Serbia before the 2016 parliamentary elections in Montenegro.

Moldova: A Scenario for Montenegro and/or Serbia

Montenegro is positioned at a socio-political crossroads. Its internal political dynamics, shaped by a polarized society and institutions that lack sufficient resilience, create multiple possible trajectories. Foreign malign influence, operating in synergy with a partocratic system, continues to slow the country’s EU integration and obstruct long-term political stabilization. Within such a complex environment, it is possible to outline both pre-election and post-election scenarios ahead of the 2027 parliamentary vote.

Given Russia’s increasingly sophisticated hybrid activities and Serbia’s role as a persistent vector of Russian influence in the region, Montenegro remains a target of foreign malign interference. From a methodological standpoint, since 2020, conditions have been gradually forming that resemble a potential Moldovan scenario in Montenegro. When observing the context of Moldova’s parliamentary elections, as well as the actors involved in efforts to destabilize the country, the parallels with Montenegro and the wider region are evident.

The identified operational patterns, instrumentalization of pro-Russian political actors, infiltration of religious institutions into the political sphere, extensive propaganda campaigns through pro-Russian media and social networks, and the deliberate fueling of social and ethnic divisions, are clearly reflected in the Montenegrin context as well. As in Moldova, the strategic objective of these activities is to weaken the country’s pro-European orientation, undermine institutional credibility, and create an atmosphere of political instability that serves the foreign-policy interests of the Russian Federation. If such processes are not identified and countered in time, Montenegro could become the next target of a major hybrid attack in the Western Balkans, with serious implications for its security and European future.

During Moldova’s parliamentary elections, priests of the Moldovan Orthodox Church played a key role in disseminating anti-EU propaganda. They were instrumentalized within the Kremlin’s hybrid efforts to influence the electoral outcome. The operation began with supposedly religious pilgrimage trips organized for groups of priests in Moldova. This network went on to establish more than twenty Telegram channels. Through these channels, anti-EU narratives were published daily, framing European integration as part of a broader agenda of a gay Europe. The unifying message revolved around defending traditional values, presented under the guise of lectures on shared faith and the love of Orthodoxy. In the Balkan context, the Serbian Orthodox Church (SPC) possesses identical mobilization capacity, making it a key intermediary of Russian influence. The SPC openly supported pro-Russian protests in Podgorica from 2014 to 2016. Its narrative of safeguarding traditional values has remained a constant before and during significant socio-political events. Ahead of the local elections in Kotor and Podgorica in September 2024, the SPC activated its full clerical network. During ceremonies and liturgies, clergy emphasized the Church’s role in protecting faith, people, and sacred heritage—an overt prelude to the electoral campaign. Senior SPC representatives aligned themselves with pro-Serbian and pro-Russian political structures, attempting to directly shape the election outcome.

Energy Resources and Hybrid Operations

The United States imposed sanctions on the Petroleum Industry of Serbia (NIS) due to its majority Russian ownership (Gazprom Neft holding 50 percent and Gazprom 6.15 percent), to limit Russian influence and curb the financing of the war in Ukraine. After several postponements, the sanctions entered into force on 9 October 2025. Beyond their economic significance (NIS controls around 80 percent of the Serbian oil market), the sanctions carry substantial implications for the projection of Russian malign influence across the Western Balkans. The financing of Russian and pro-Russian media in Serbia, coupled with Serbia’s energy dependence on Russia, has enabled the Kremlin’s hybrid operations to be carried out from Serbian territory without meaningful obstacles. However, should Belgrade eliminate Russianownership in the energy sector through the sale or buyback of Gazprom Neft and Gazprom shares, the Kremlin is likely to activate alternative channels to preserve and strengthen its influence. Official Moscow has repeatedly expressed strong support for the Serbian authorities amid civic and student protests following the collapse of a canopy structure in Novi Sad. By dispatching FSB agents to Serbia, who publicly claimed that a sound cannon had not been used during the 15 March protest, and through statements from the SVR alleging that a color revolution was being prepared, Moscow’s political backing has been clear. The government in Belgrade is using the narrative of a color revolution to downplay protests against corruption and portray them as an EU-sponsored project aimed at toppling the Serbian leadership.

At the same time, the presence of pro-Russian structures within the student protests in Serbia is undeniable and illustrates that Moscow is playing a double game in the current political environment. Despite the Kremlin’s narrative of a Western-backed color revolution, pro-Russian groups with matching iconography have been active at student demonstrations since January 2025. Self-proclaimed war veterans have positioned themselves as supporters of students and citizens engaged in the struggle for civil rights. The most prominent among them—Nenad Stanić and Siniša Jevtić—previously expressed open support for Russia’s aggression against Ukraine.

These individuals appear at virtually all gatherings and are responsible for introducing Russian wartime symbols into the protests. The flag of the Russian Orthodox Army, associated with the Battle of Kulikovo and now one of the symbols of Russian aggression in Ukraine, has become a visible element at civic demonstrations in Serbia. Digital and information spaces also play a significant role in shaping protest dynamics. Several YouTube channels have used the topic of student and civic mobilization to amplify pro-Russian and anti-Western rhetoric, reinforcing destructive narratives across Western Balkan societies. Channels such as X33, Glas Javnosti, HelmCast, Balkan Info Podcast kod Brane serve as platforms for promoting an alternative vision of Serbia in which the EU and the West are portrayed as existential threats to national identity, sovereignty, and traditional values. Russia and various alternative alliances, by contrast, are presented as natural and desirable partners for Serbia’s future

The infrastructure for destabilizing the region is already in place. The increased activity of pro-Russian structures, the Serbian Orthodox Church, sympathetic media outlets, and coordinated social media networks suggests that the Kremlin is preparing actions that correspond to the wider geopolitical moment and the outcome of the NIS sanctions. The number of Russian diplomats in Serbia rose from 54 before the invasion of Ukraine to 68 by mid-2025. Many of the newly arrived diplomats had been expelled from EU countries following Russia’s aggression. Additionally, between 2022 and 2025, around 200 Russian nationals acquired Serbian citizenship, including close associates of President Vladimir Putin. Considering Montenegro’s final stage of EU accession, the regular parliamentary elections scheduled for 2027, and the ongoing social polarization in Serbia, including the possibility of snap elections, the conditions resemble those of Moldova before the 2025 vote. The appointment of Aleksandr Lukašik as Russia’s ambassador to Montenegro reinforces this trajectory. Between 2016 and 2022, before Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine, he served as chargé d’affaires at the Russian Embassy in Kyiv.

Events that represent strategic turning points for European states remain key targets of Russian asymmetric and hybrid operations. The Moldovan scenario, characterized by round-the-clock disinformation and polarizing narratives spread through social networks, has already been replicated during elections in the Czech Republic. Researchers there found that sixteen pro-Russian disinformation outlets produced more content than all traditional media combined. In France, five months before local elections, investigators uncovered a network of 85 pro-Russian disinformation websites designed to mimic the visual appearance of credible French news platforms.

The installation of a pro-Russian network in Serbia is spilling over into Montenegro. On 26 October 2025, the Russian Historical Society—founded by SVR Director Sergei Naryshkin—established its Serbian branch. The director of the Belgrade office is former BIA chief Aleksandar Vulin. The timing of the society’s founding coincides with the NIS sanctions and the upcoming electoral cycle in Serbia. The statements delivered at the founding ceremony were symptomatic, promoting the concept of the Serbian World and glorifying the Kremlin’s malign doctrine. Among the attendees was Metropolitan Metodije Ostojić of the Budimlje–Nikšić diocese. In May 2025, the Holy Synod of the Serbian Orthodox Church granted him the title of metropolitan, after which he intensified activities that polarize Montenegrin society and distance it from EU norms. Ostojić is one of the leading advocates of rehabilitating the fascist Chetnik movement from the Second World War. In August 2025, he led a group that erected a monument to Chetnik commander Pavle Đurišić near Berane.

Within this broader context, the cultural-religious manifestations promoted by the Serbian Orthodox Church, particularly those linked to the campaign to restore the Chapel on Mount Lovćen, function as a soft introduction to potential societal destabilization. Through the commemorations marking 100 years since the reconstruction of Njegoš’s chapel, an information environment is being created that could paralyze Montenegro’s EU accession path and further deepen social divisions. Representatives of the SPC have announced such events repeatedly. At the same time, pro-Serbian right-wing actors in Montenegro have received official commendations from the Serbian Armed Forces.

Volunteer Camps in Russia

The Montenegrin police operation Lugansk, which resulted in the arrest of individuals suspected of participating in foreign armed formations, exposed members of pro-Russian and pro-Serbian right-wing groups active in Montenegro. The phenomenon of volunteers from the Western Balkans travelling to the Ukrainian frontline to fight alongside Russian forces represents a multilayered security risk for the region. A central element of this risk is the existence of a recruitment hub known as the Center of Russian Patriots in Khanty-Mansiysk, located in central Russia. This facility functions as a logistical and ideological mobilization point for volunteers from across the Western Balkans. Vladimir Avramović—formerly a member of Serbia’s special unit Cobras —was recruited through this center and now fights with the 137th Assault Brigade stationed in Donbas. After returning from the front for the first time, he stated in interviews with Russian media that several Serbs fighting in the same brigade had been recruited through the Center of Russian Patriots in Khanty-Mansiysk.

Similarly, Serbian national Bojan Odžić became a veteran of the so-called Special Military Operation after returning wounded from the battlefield. Following the awarding of a medal for bravery, Odžić stated that nineteen volunteers applied to the same Center in March 2025 due to its efficiency and rapid deployment to the front. Russian media have also reported that Montenegrin nationals were recruited through this facility. Available video footage shows Serbian citizens wearing uniforms marked with the emblem of the Russian Orthodox Army—a symbol visible among pro-Russian elements at civic protests in Serbia

Moreover, the Defenders of the Fatherland Foundation in Russia has been tasked with assisting families of participants in the so-called Special Military Operation who are listed as missing. Under a presidential decree, the Foundation is authorized to provide psychological and psychotherapeutic support, help families access social benefits and offer free legal assistance. In practice, however, the Foundation’s centers—spread across Russia—serve not only as support structures for relatives of missing soldiers but also as recruitment points.

This recruitment dynamic poses significant risks in terms of regional radicalization. The return of volunteers with combat experience, deeply internalized ideological narratives, and strengthened ties to Russia increases the potential for destabilization. Such individuals contribute to the growth of extremist networks, the intensification of public polarization, and the instrumentalization of geopolitical loyalties within domestic political processes. In this environment, recruitment structures operate as channels through which regional tensions can be further amplified.

Institutional Challenges and Future Directions

Russian hybrid activities across Europe have visibly intensified through the expansion of propaganda operations and political pressure. It is therefore realistic to expect that such activities will further escalate in Serbia. The potential loss of Russian ownership in the Petroleum Industry of Serbia represents a key trigger for this dynamic, since Moscow views the energy sector not merely as an economic asset but primarily as a geopolitical instrument of influence.

If this mechanism were to be significantly weakened or fully dismantled, Russia would likely respond by intensifying malign activities, strengthening media and information operations, and amplifying political and social support for pro-Russian actors. Through these efforts, Moscow aims to send a clear message to the West: no major decisions concerning Serbia can be made without Russian consent. As a result, Serbia will likely face increased pressure and destabilization attempts, while Russian structures will seek to preserve or compensate for their influence in the energy sector to demonstrate that they still possess the capacity to shape strategic developments in both Serbia and the wider region.

Within this context, hybrid activities will probably spill over into Montenegro—particularly given that the country is in the final phase of its EU accession process and is heading toward regular parliamentary elections in 2027. Former Russian ambassador to Montenegro, Vladislav Maslenikov, stated in 2023 that EU enlargement into the Western Balkans “draws these countries into confrontation with Russia.”

The incident in Zabjelo, Podgorica, in November 2025—which triggered anti-migrant protests and the formation of so-called “citizens’ patrols”—illustrates how disinformation and narrative manipulation can shape public perception, deepen divisions, and generate widespread mistrust. It also demonstrates how easily the most radical segments of Montenegrin society can be mobilized within a short time frame.

Following the pattern observed in Moldova, actors who already possess well-developed influence infrastructure in the region—through media networks, political and parapolitical organizations and powerful religious structures—could attempt to further polarize Montenegrin society by instrumentalizing the Serbian Orthodox Church and engaging para-state elements from Serbia. The objective of such activities would be to weaken Montenegro’s pro-European trajectory, heighten tensions between identity and political blocs, and reinforce the narrative that any movement toward the West inevitably leads to domestic instability.

The sudden installation of a monument to the fascist collaborator Pavle Đurišić—organized by the Serbian Orthodox Church—and the passive response of Montenegro’s security sector represent both a tactical and strategic test for similar scenarios in the future.

Within this security environment, Montenegrin institutions must establish the systemic fight against foreign interference, disinformation, and malign influence as one of their highest strategic priorities. This need was emphasized in the European Commission’s most recent report, which highlighted the importance of strengthening institutional resilience and improving national capacity to detect and counter hybrid threats.

Nationalist rhetoric, Russian disinformation campaigns, and religious influence are already deeply rooted in segments of Montenegrin society, creating fertile ground for potential radicalization and the recruitment of volunteers for Russian hybrid activities and Russian military or paramilitary structures.