The project for the construction of a wastewater treatment plant in Botun has evolved from an infrastructural and environmental issue into a political crisis. In the absence of timely and clear information about the technology, environmental impact assessment procedures, and decision-making phases, the public space was left open to speculation and political instrumentalization.

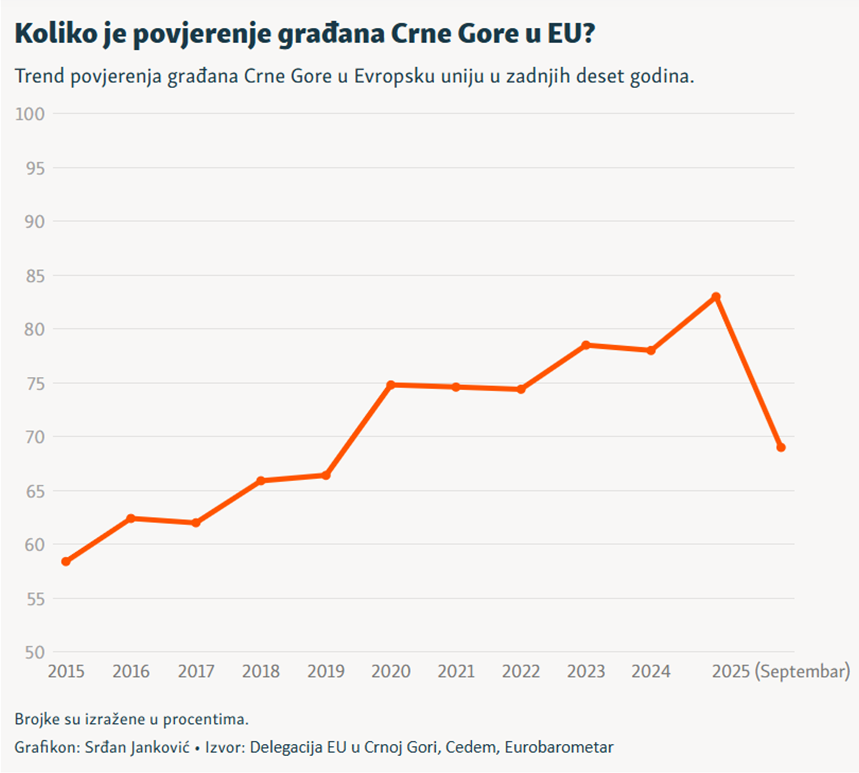

Such a vacuum represents fertile ground for the spread of disinformation, as fear and uncertainty become the dominant framework through which citizens interpret the project. Narratives are formed ad hoc, through political clashes and media sensationalism. This leads to the erosion of public trust in state institutions and in the process of EU integration. Available research consistently shows a low level of citizens’ trust in state institutions, confirming that this is a long-standing problem present across multiple research cycles. Consequently, citizens often seek alternative interpretations of politics through social networks and informal media.

Additionally, this is confirmed by the latest Eurobarometer data from September 2025, which showed the first significant decline in trust in the European Union (EU) since the category was first measured. Trust among Montenegro citizens in the EU decreased by as much as 14 percentage points over six months (from 83% to 69%), according to research conducted for the European Commission.

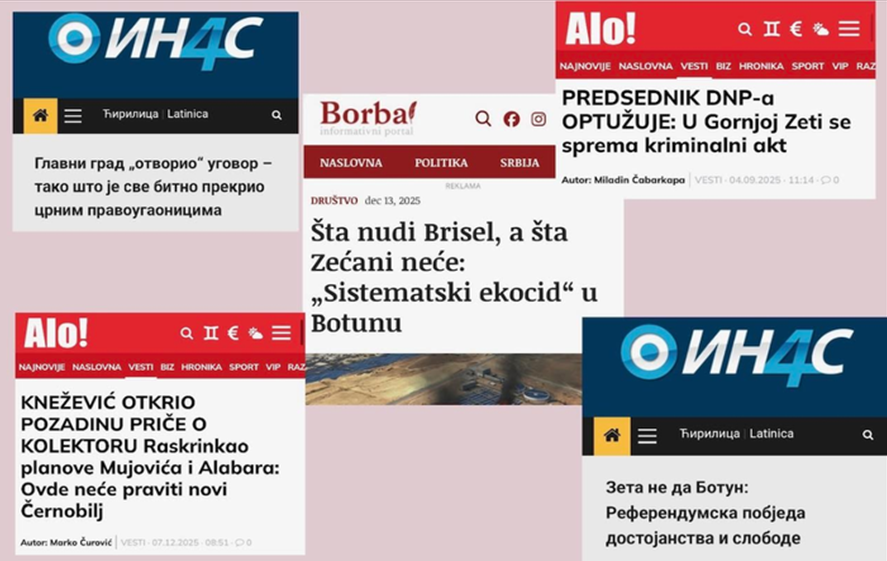

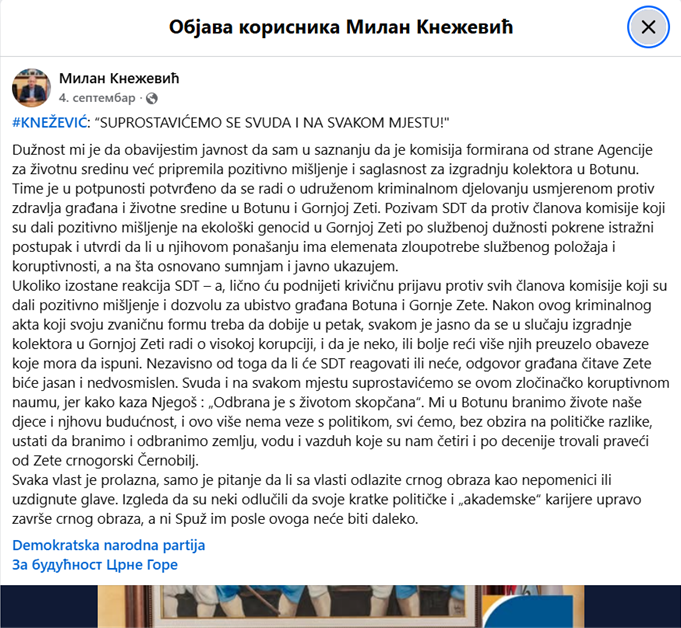

In the Botun case, from the very beginning, narratives were created claiming that the EU and its representatives directly impose decisions and that domestic institutions do not act in the interests of citizens. Such narratives were actively promoted by Milan Knežević, leader of the Democratic People’s Party (DNP), and by pro-Serbian portals Borba, Alo Online, and IN4S. Knežević portrayed the EU Ambassador to Podgorica as the real decision-maker in the country, relying on an established anti-EU narrative that depicts the European Union as a threat to national sovereignty. By invoking the European Public Prosecutor’s Office (EPPO/Kövesi), Knežević shifts public focus toward polarizing topics, framing the narrative as a conflict between citizens and external influence. Sensationalist media headlines such as “Knežević Exposed the Plans” or “A Criminal Act in Gornja Zeta” further amplify emotional reactions. On the ground, this resulted in the mobilization of local protests.

The discourse formed around the construction of the treatment plant in parts of the media and in public statements by certain political actors demonstrates a pattern that goes beyond legitimate citizen concern. The dominant construct is that the wastewater treatment plant is not a public project but a means of deliberately endangering citizens’ health, backed by hidden political-economic connections.

Tendentious media content about “exposing the background,” “secret plans,” and a “new Chernobyl” does not serve to inform but to project emotion. The term “Chernobyl,” stripped of any technical or regulatory connection to the collector, functions as a symbol of absolute catastrophe. In this way, rational debate about standards and oversight is replaced by fear and a sense of threat. At the same time, the project is personalized by naming specific political and business actors, reducing public policy to a moralized conflict between culprits and victims.

Further escalation of the discourse is evident in the trivialization of analogies that reduce a complex infrastructural problem to personal conflict and crude humor. Such messages do not seek clarification but produce a clear division between “us,” who are threatened and deceived, and “them,” who impose solutions without legitimacy. Questions of location and public interest are lost behind this symbolism.

The most radical layer of the narrative appears in formulations such as “ecological genocide,” “a license to kill citizens,” “a criminal act,” and “high corruption.” The use of international law and criminal law terminology in the context of an infrastructural project lacks factual foundation. If a project is framed as genocidal, there is no space for dialogue—only resistance remains. Such a context pre-emptively criminalizes all actors involved in the process and legitimizes extra-institutional pressure as the only acceptable response.

Significantly, the most serious accusations and most dramatic formulations are strongly amplified through tabloids outside Montenegro, thereby fitting the local case into a broader pattern of delegitimizing domestic institutions. Certain portals, in an unobjective, unprofessional, and continuous manner, use value-laden terms such as dignity, freedom, and resistance to portray one side as morally superior and any disagreement as an attack on the community’s fundamental values. Rhetorical questions, quotation marks, and visually powerful metaphors of concealment are used to present insinuation as fact and suspicion as proof.

Consequently, the presented development of events benefits a broader narrative according to which Montenegro is not ready for Europe, its institutions are inherently illegitimate, and European standards are merely a façade for hidden interests. Such an outcome also suits external actors who benefit from maintaining the status quo or from completely halting Montenegro’s EU integration. Slowing this path reduces pressure to implement reforms and leaves space for preserving alternative political and security influences. Political power centers in the region, and indirectly beyond, have a strategic interest in ensuring that convergence toward the EU remains slow. An additional layer of legitimization of this narrative is achieved through the involvement of public figures from Serbia. A clear example is the public appearance of former Serbian MP Lazar Ristovski, whose comments regarding Botun go beyond the framework of civic solidarity and enter the realm of political interference. Such messages, especially when coming from outside, further amplify distrust within Montenegro.

MN: The absence of an institutional response as a key catalyst of the crisis

The Botun case has shown that strategic communication must be an integral part of public policy, ensuring timely, clear, and consistent interpretation of decisions, risks, and procedures. The impression is that the problem lay less in the decision to build the wastewater treatment plant itself than in the way competent institutions communicated with citizens—or rather, in what they failed to communicate or do.

Citizens of Botun and the wider public were not timely informed about the project’s objectives, the reasons for choosing the location, or the long-term benefits for health and the environment. Instead of continuous dialogue, institutions reacted only after dissatisfaction had escalated, creating the impression that decisions were made behind closed doors. Even the later statement by Podgorica Mayor Saša Mujović, acknowledging communication failures, confirms that no strategic approach existed from the outset and that improvisation occurred under pressure.

A particular problem was the absence of a publicly available and transparent project timeline. Citizens were not presented with the phases of planning, environmental impact assessment, public hearings, deadlines for the start and completion of works, or the roles of individual institutions in the process. Instead, information was communicated piecemeal, through individual media statements that were often contradictory or temporally misaligned. Such uncertainty fueled suspicion and the feeling that something was being hidden, even though there was no clear evidence for this.

One of the most serious institutional failures was the lack of translation of technical and expert information into a language understandable to citizens. Environmental impact assessments, technology descriptions, and risk-control procedures remained locked in bureaucratic and technical jargon. Citizens were not given simple, concrete explanations of how the plant functions, which technologies are used, what the real risks are, and what constitutes myths. In such an environment, associations with “Chernobyl” or “ecological genocide” were more readily accepted by the public because institutions did not offer a comprehensible alternative.

There was also no central source of information; instead, information was scattered across statements from various institutions, politicians’ remarks, and media reports. As a result, citizens were directed toward social networks and portals with pronounced political agendas, which significantly complicates distinguishing facts from interpretations. Even the publication of key documents and contracts came late and appeared more as a reaction to pressure than as proactively planned transparency.

Moreover, institutions did not respond promptly to disinformation and manipulative narratives. Claims about threats to public health, criminal activities, and external imposition of decisions spread for days and even weeks before being debunked. When responses finally arrived, they were delayed and often defensive, which called their credibility into question. In some cases, international actors even had to refute false claims, indicating that domestic institutions did not assume full responsibility for protecting the public sphere from disinformation.

The lack of timely engagement by the Government of Montenegro in communicating with citizens further increased distrust in domestic institutions. This also weakens the European narrative, creating the impression that European standards are merely a pretext for non-transparent decisions. In this sense, Botun is not an isolated incident or exception but a warning that without clear, open, and responsible institutional communication, any public project can become fertile ground for radicalization, disinformation, and loss of trust in democratic processes.

Therefore, the case of constructing the collector in Botun clearly indicates the need to strengthen strategic communication within public administration by establishing a dedicated strategic communication unit, following the example of EU member states. The goal is to protect citizens from manipulation while simultaneously strengthening the resilience of the EU integration process, which is already exposed to disinformation. Pressures are expected to increase as Montenegro approaches full EU membership. It is therefore necessary to take urgent steps to strengthen citizens’ trust in institutions. This ensures coherent messaging to the public and creates sustainable support and greater social acceptance of public projects. Otherwise, there is a real threat to Montenegro’s democratic stability and European perspective.