In the Podgorica neighborhood of Zabjelo, on October 26, 2025, a physical altercation occurred between a group of local young men from Podgorica and, according to police reports, four nationals of Azerbaijan and Turkey. Cold weapons were used during the fight, and one Podgorica resident sustained a minor stab wound. The police arrested the Azerbaijani and Turkish nationals; however, the investigating judge of the High Court in Podgorica revoked their detention, ruling that there was no reasonable suspicion that the two had committed the criminal offense of attempted murder against the Podgorica resident.

This incident coincided with pre-existing tensions in Montenegrin society, fueled by narratives about Islamization, the alleged influx and takeover by foreigners, and the politicization of migration and identity issues. These dynamics have led to acts of vandalism, violence, and hate speech. In this sense, the incident cannot be viewed merely as a criminal matter but rather as a reflection of deeper systemic weaknesses—institutional, media-related, and political. If such phenomena are not addressed and prosecuted in an appropriate and just manner, Montenegro may witness renewed and even more destructive cycles of social polarization.

The Zabjelo incident triggered a wave of protests framed as citizens’ defense actions. However, the background of these gatherings was clerical-nationalist in nature, as confirmed by the slogans heard during the rallies—many of which were rife with hate speech and xenophobia. Political party statements, reporting by pro-Serbian media outlets in Montenegro, as well as Serbian regime-affiliated media, known for spreading disinformation and false narratives, all contributed to heightening tensions. These factors, compounded by the amplification of hate speech and disinformation on social media, have fueled the rise of clerical-nationalist activity within society. In Podgorica, Bar, and Herceg Novi, restaurants and vehicles owned by Turkish citizens were set on fire. Consequently, what began as an isolated security incident with elements of a criminal offense has evolved into a national—and even regional—security concern, marked by clear aspects of intimidation and collective retaliation against a specific group.

Visa Regime

Faced with public pressure and an extraordinary security situation, the Government of Montenegro resorted to introducing visas for Turkish nationals. Prime Minister Milojko Spajić announced the decision immediately after the outbreak of protests via social media, emphasizing that it would be adopted under an urgent procedure. At an extraordinary government session, the visa-free regime with Turkey was formally suspended until further notice — temporarily, according to the official explanation. The Government justified the measure on security grounds, citing the need to control the entry and stay of foreigners and to preserve public order, while noting that the visa regime for Turkish citizens would be temporary and that a fast-track visa issuance procedure would be introduced to mitigate the impact on the economy and tourism.

The decision carries three layers of consequences. The first is domestic political: the government demonstrates decisiveness but simultaneously risks normalizing the narrative that the Turkish community represents a security threat, opening the door to selective stigmatization and ethnic profiling.

The second is economic: Turkey is an important source of investment, real estate purchases, and seasonal spending, while Montenegro relies heavily on its image as an easily accessible Adriatic destination. Entry restrictions — even if formally temporary — pose a reputational risk that Montenegro is starting to close its doors, which could directly affect the tourist season and revenues in hospitality, air transport, and short-term rentals, especially if Turkey responds with reciprocal measures against Montenegrin citizens or if some potential visitors simply redirect their plans to other Mediterranean destinations.

The third layer is foreign policy: the government also ties this decision to alignment with European standards, as the EU expects candidate countries to harmonize their visa policies with the Schengen list. In practice, this means that Montenegro would eventually have to introduce visas not only for Turkey but also for Russia before closing negotiation chapters. The government now presents this decision as a step toward meeting EU criteria, not merely a reaction to street pressure.

However, the key weakness of the measure is that introducing visas acts more as a political gesture toward the domestic audience than as a real solution to the problem being exploited to fuel tensions, the already present community of foreign nationals. Montenegro currently hosts several tens of thousands of foreigners with legal status, including, according to data from the Ministry of Interior, around 13,800 Turkish citizens with temporary residence and 87 with permanent residence, while there are even more Russian citizens — about 23,330. It is important to note that the actual number of foreigners is significantly higher than official MUP statistics suggest.

In the case of Turkish nationals, the post-incident narrative was immediately criminalizing and ethnically charged (Turks attacking, Turks taking over Podgorica). For Russian nationals, such an aggressive labeling campaign did not occur, even though their numbers are greater, suggesting that the security argument has not been applied consistently but rather selectively politicized. In other words, the visa regime may limit new inflows but does not address existing structural issues: weak migration control, the issuance of temporary residence permits through property purchases or fictitious companies, and the instrumentalization of foreigners in political and identity conflicts. This dynamic carries a long-term risk that certain migrant communities could become convenient internal scapegoats whenever the authorities need a quick and visible response — to the detriment of social cohesion and Montenegro’s international relations.

For that reason, alongside the introduction of visas, more comprehensive measures are needed to address the underlying issues:

- Enhanced monitoring and verification of foreigners already residing in Montenegro, especially those involved in suspicious activities. This includes better coordination among the police, prosecution, and intelligence services in tracking organized criminal groups.

- Swift and decisive enforcement of the law: sanctioning anyone who violates regulations, whether local citizens or foreigners. This means prosecuting those responsible for violence and hate speech, as well as deporting or denying entry to foreigners who cause problems in the country.

- Improvement of immigration policy: clearly defining the conditions for obtaining residence permits, monitoring the expiration of tourist stays, and preventing abuses (e.g., fake study visas or fictitious companies). The government has already initiated amendments to the Law on Foreigners, which should bring greater order to the area of temporary residence and employment of foreign nationals.

Thematic Clusters in the Public Sphere

Between October 26 and October 30, 2025, a total of 1,660 articles directly or indirectly related to the incident in Podgorica were published across domestic and regional media. Serbian media outlets dominated the coverage with 672 publications, while Montenegrin media produced 592 articles on the topic, framing the incident primarily through security and socio-political perspectives

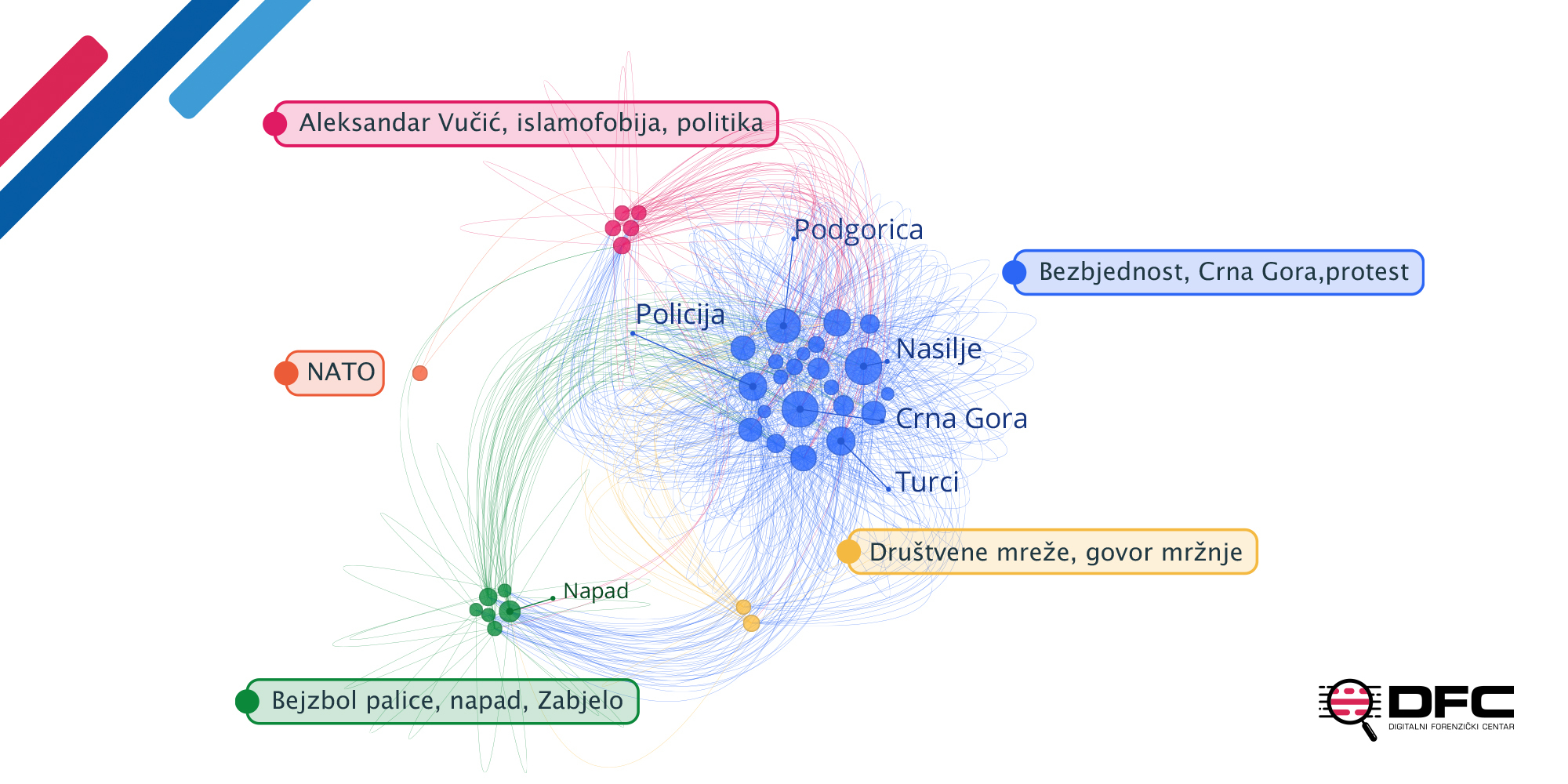

The Digital Forensic Center (DFC) software generated a network of thematic clusters within the virtual space. The visualization of these clusters illustrates a network of key concepts and their interconnections across media and online platforms during the period from October 26 to 31, 2025, immediately following the incident in Podgorica, in which a Montenegrin citizen was injured in a confrontation with nationals of Turkey and Azerbaijan.

The largest and most prominent node — the blue cluster — encompasses terms such as Podgorica, violence, police, Turks, incident, and arrests, representing the core narrative that dominated media coverage. Within this framework, the media primarily focused on the security dimension of the event — police responses, the arrest of foreign nationals, official statements, and subsequent institutional measures. This cluster reflects the theme of perceived threat, emphasizing fear, police control, and public safety concerns in the capital.

The yellow cluster links terms such as social networks, hate speech, protests, xenophobia, and migrants. It represents the reactionary layer of online discourse, where the incident acted as a trigger for hate speech and calls for public protests.

The green cluster gathers terms like attack, baseball bats, knife, migrants, and violence, focusing on the physical confrontation in Zabjelo. This segment of the network is dominated by short-form news and sensationalist headlines, indicating the tabloidization of the incident and the rise of emotional tension in the public sphere. The green cluster overlaps with the blue node through the terms attack and police, confirming that security and sensationalist narratives operated in a complementary manner.

The red cluster includes terms such as Aleksandar Vučić, NATO, Islam, and Serbia, pointing to the regional politicization of the incident. This part of the network features content from pro-Serbian and pro-Russian media, which linked the incident in Montenegro to geopolitical narratives, the alleged consequences of NATO policies, the endangerment of Orthodoxy in the region, and the broader EU migration agenda. It represents a typical example of a transnational narrative that exploits a local incident as a framework for broader political messaging and propaganda objectives.

Finally, a smaller, isolated light-blue cluster groups terms such as security, Montenegro, and region, representing analytical articles that sought to rationalize the event and place it within a broader context of institutional accountability.

Culmination of the Negative Campaign

The negative campaign targeting Turkish nationals is not a new phenomenon in Montenegro. For some time, narratives have been circulating claiming that Turks are occupying Montenegro, that 100,000 Turks currently reside in the country, and even that Turkish nationals are abducting children. These disinformation narratives were spread by Milan Knežević, one of the leaders of the parliamentary majority. Similarly, Nebojša Medojević propagated the narrative of the “Islamization of Montenegro,” alleging that the Montenegrin Ministry of Foreign Affairs sought to increase the percentage of the Muslim population at the expense of Montenegro’s Christian majority. These narratives were disseminated by media outlets such as Borba, Alo Online, IN4S, as well as several Belgrade-based tabloids.

According to official data from the Ministry of Interior, Montenegro hosts approximately 13,800 Turkish citizens with temporary residence, and 87 with permanent residence.

Following the Zabjelo incident, there was a visible escalation of activity among right-wing and clerical-nationalist parties, Orthodox brotherhoods, media outlets, and online trolls. This led to the formation of so-called street patrols. Participants were mostly dressed in dark clothing, wearing masks, balaclavas, and hoods. Individuals identified as members of extremist groups linked to the Serbian Orthodox Church and the party of the Speaker of Parliament, Andrija Mandić, were particularly active in organizing and mobilizing participants. Ahead of the protests, Podgorica police detained 11 individuals, nine of whom were minors. According to the Police Directorate, they had planned to appear in front of the Government building wearing balaclavas and carrying torches.

Four well-known activists and politicians participated in the anti-migrant rally held in front of the Government of Montenegro in downtown Podgorica on October 28. Chants such as Turks Out, Whoever Doesn’t Jump Is a Turk, and We Don’t Want Migrants, Turks Won’t Walk Our Streets were heard during the gathering. Among those identified in photographs were Goran Milić and Zoran Ušćumlić, both officials of the ruling New Serbian Democracy (NSD) party, as well as Milivoje Brković and Boban Radević, members of the Podgorica local assembly.

One of the participants in the street patrols formed after the Zabjelo incident was Slavko Perošević, a Chetnik vojvoda and Srebrenica genocide denier. Perošević was one of the organizers of a memorial service for the 1st and 2nd Durmitor Chetnik Brigades in cooperation with the Serbian Orthodox Church at the Podmalinsko Monastery on June 7, 2025. He also helped organize the setting of a monument to WWII Chetnik collaborator and war criminal Pavle Đurišić in August of the same year. During the protest march on October 27, he stated that we face the same monster that once threatened our children, mothers, and wives,” warning that “whoever raises a filthy fist against Montenegro will be met with the blow of a hammer.

Vladislav Dajković, President of Free Montenegro and head of the Civic Service of the Capital City, advanced the narrative that the arrival of Turkish citizens in Montenegro was not mere economic migration, but rather an organized state project of neo-Ottomanism, asserting that the Turkish world has knocked on Montenegro’s door.

The Constitution of Montenegro prohibits any incitement of hatred or intolerance based on national, racial, religious, or other personal grounds. Article 370 of the Criminal Code prescribes penalties for public incitement to hatred, ranging from a fine or up to two years in prison in minor cases, to ten years of imprisonment if the act involves violence, threats, or causes serious harm to life, health, or property.

Anti-EU Narrative

The escalation of the anti-migrant narrative in Montenegro has acquired a new political function — it has been instrumentalized as a lever against European integration. The core construction of this narrative claims that, upon joining the EU, the majority of Montenegrin citizens will emigrate, while migrants from Turkey, Azerbaijan, and wider Asia will replace them. The EU is thereby portrayed as a system that encourages the departure of our people and imposes others. This framing combines three layers of fear — demographic panic, cultural replacement, and loss of sovereignty. In practice, the narrative seeks to portray the EU not as a solution but as the source of Montenegro’s problems, while discrediting the pro-European course as naïve, dangerous, or even treacherous.

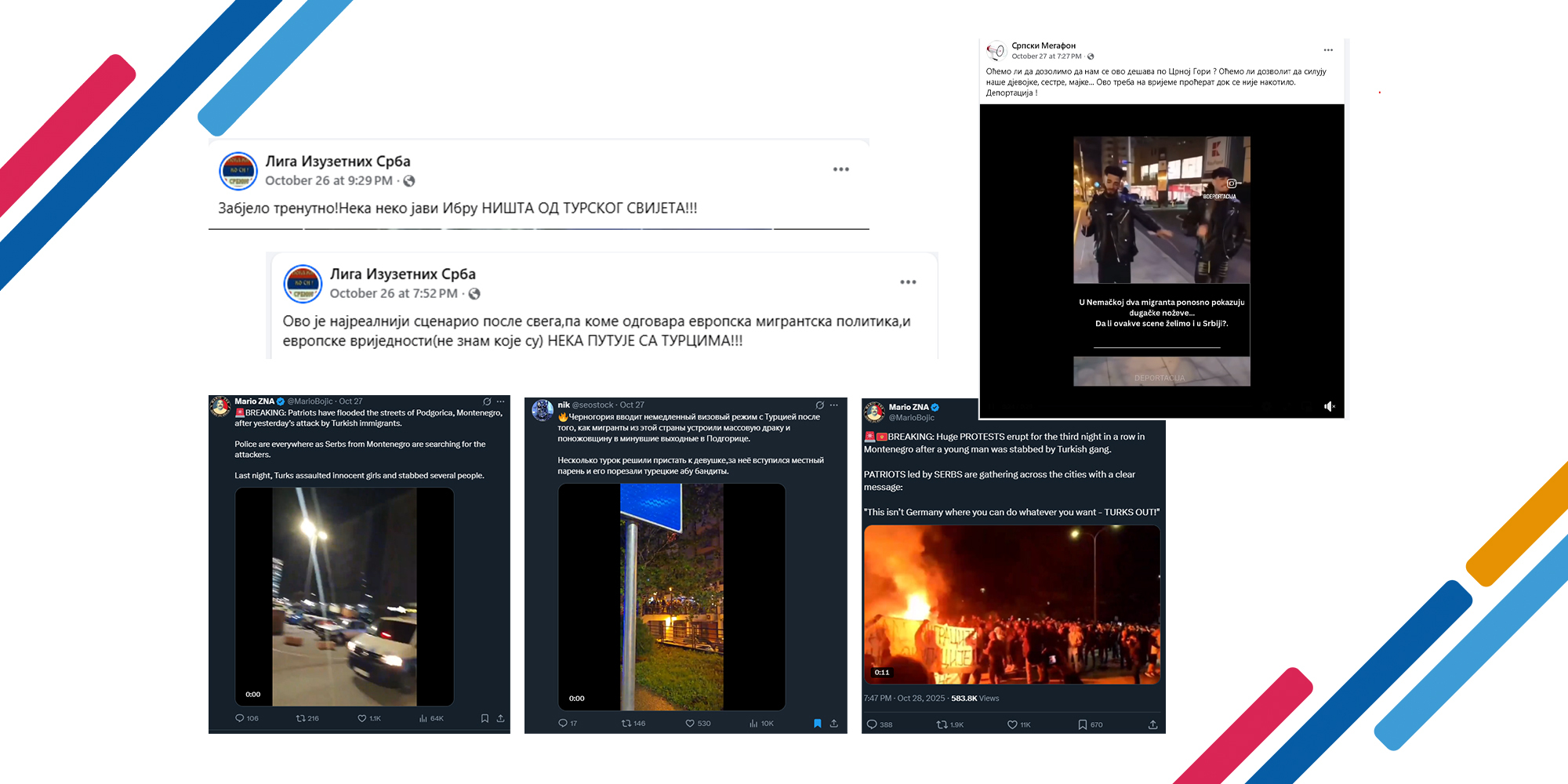

Pro-Serbian and pro-Russian media pages and accounts on X and Facebook exploited the conflict between foreign nationals and Montenegrin citizens to amplify anti-EU narratives and disinformation. The most active page was Srpski Megafon, which shared videos allegedly from Germany showing migrants holding knives, accompanied by the caption: Will we allow this to happen in Montenegro? Another post claimed that migrants from Arab countries are committing group assaults and that “the same awaits Montenegro. On October 25, the page asserted that EU accession will bring Turks, Nepalis, and Arabs to Montenegro, leading to burglaries, assaults, and chaos. Other pages — Liga izuzetnih Srba, NVO Serdar, and Srbi u Crnoj Gori — were among the most active in heightening tensions. The Liga izuzetnih Srba page shared videos proclaiming There will be no Turkish world, while another video claimed that Montenegro will accept migrants from the UK and that those who support European migrant values should move in with the Turks.

From abroad, pro-Russian and pro-Kremlin accounts used the disturbing scenes from Podgorica to launch a coordinated disinformation campaign, promoting anti-EU and pro-Russian narratives. Profiles that regularly disseminate Kremlin-aligned geopolitical content shared videos from Podgorica claiming that protesters shouted at migrants: This is not Germany, where you can do whatever you want. Core disinformation relied on emotional manipulation, falsely suggesting that the protests were sparked by migrant attacks on girls and“multiple stabbings. Key accounts driving these narratives included MarioZNA, SlavicNetwork, and a Russian profile nik@seostok, known for promoting radical anti-migrant rhetoric. Their posts amassed over 400 shares and 200,000 views on the social platform X. This pattern of activity is not an isolated case, but part of a broader pro-Kremlin bot and troll network that exploits significant regional events to advance anti-EU propaganda. Migrant-related or inter-ethnic incidents are used to frame EU integration as a threat to national identity, security, and social stability.

The mechanism of operation follows a predictable pattern. Individual incidents involving foreigners — particularly those fitting stereotypes of Eastern migrants — are framed as paradigmatic examples of an impending imported crisis. Every physical altercation, criminal report, or visually dramatic scene is reframed as evidence of an incoming wave of imported problems. The subsequent message warns that the EU forces open borders, quotas, and relocations, even though the accession process and EU acquis require the opposite: regulated procedures, strengthened border management, asylum standards, and return agreements — in other words, more control, not less.

The next stage of the narrative is emotional simplification: our people will leave for jobs abroad, and only foreigners will remain here. In this way, complex issues such as labor markets, productivity, wages, and institutional quality are obscured. The core strength of this narrative lies in its ability to merge legitimate public concerns with false causal explanations.

A Successfully Expanded Overton Window

The incident in the Podgorica neighborhood of Zabjelo serves as a paradigmatic example of how a localized security event of limited scope can become a platform for broader political, ideological, and media instrumentalization. Within days, public focus shifted from concrete facts about the altercation to emotionally charged narratives that heavily shaped public perception. Media outlets, political structures, and social media users leveraged the event to reinforce existing divisions and create new lines of conflict, turning an isolated case into a symbol of alleged threats to national, religious, and cultural identity.

Clerical-nationalist groups, right-wing organizations, and certain political actors seized the opportunity to mobilize supporters under the guise of defending Montenegro from foreigners and the supposed dangers of migration. The incident thus became a catalyst for the spread of hate speech and intolerance, as well as a test of the state’s institutional capacity to respond to such hybrid threats. Instead of being used to calm tensions, the public sphere turned into an arena of emotional and political manipulation, blending nationalist, anti-Islamic, and anti-EU narratives.

Analysis of thematic clusters indicates that the information space in the days following the incident was deeply polarized. The Podgorica event clearly demonstrates how different actors — media, political structures, and social networks — constructed their own narratives, transforming a single event into a broader political and identity conflict. The incident became a powerful catalyst for hate speech in the public sphere, where certain actors exploited it to stir emotions and fuel xenophobia. Simultaneously, the digital environment was flooded with disinformation and manipulative narratives, which further escalated tensions and deepened polarization within Montenegro’s information ecosystem.

The incident in Podgorica also illustrates the successful expansion of the Overton window in Montenegrin society — a process through which radical ideas, hate speech, and clerical-nationalist rhetoric have gradually been normalized and accepted in public discourse. This shift stems from years of institutional tolerance toward extremist rhetoric, glorification of war criminals, and unchecked hate propaganda. The consequences of this institutional passivity are now evident in the public’s reaction to the Zabjelo incident, where xenophobia and political extremism are expressed openly and without institutional condemnation.

This case underscores the urgent need for Montenegro to strengthen mechanisms for identifying and sanctioning hate speech, as well as to invest in education and media literacy to prevent further erosion of socially acceptable discourse. Otherwise, there is a real risk that extremist ideas will take permanent root, evolving into a systemic threat to the country’s democratic stability and European future.