After the change of government in Montenegro in 2020, pro-Serbian and pro-Russian structures within the new ruling majority revived the issue of amending the Law on Montenegrin Citizenship, actively promoting the idea of introducing so-called dual or multiple citizenships.

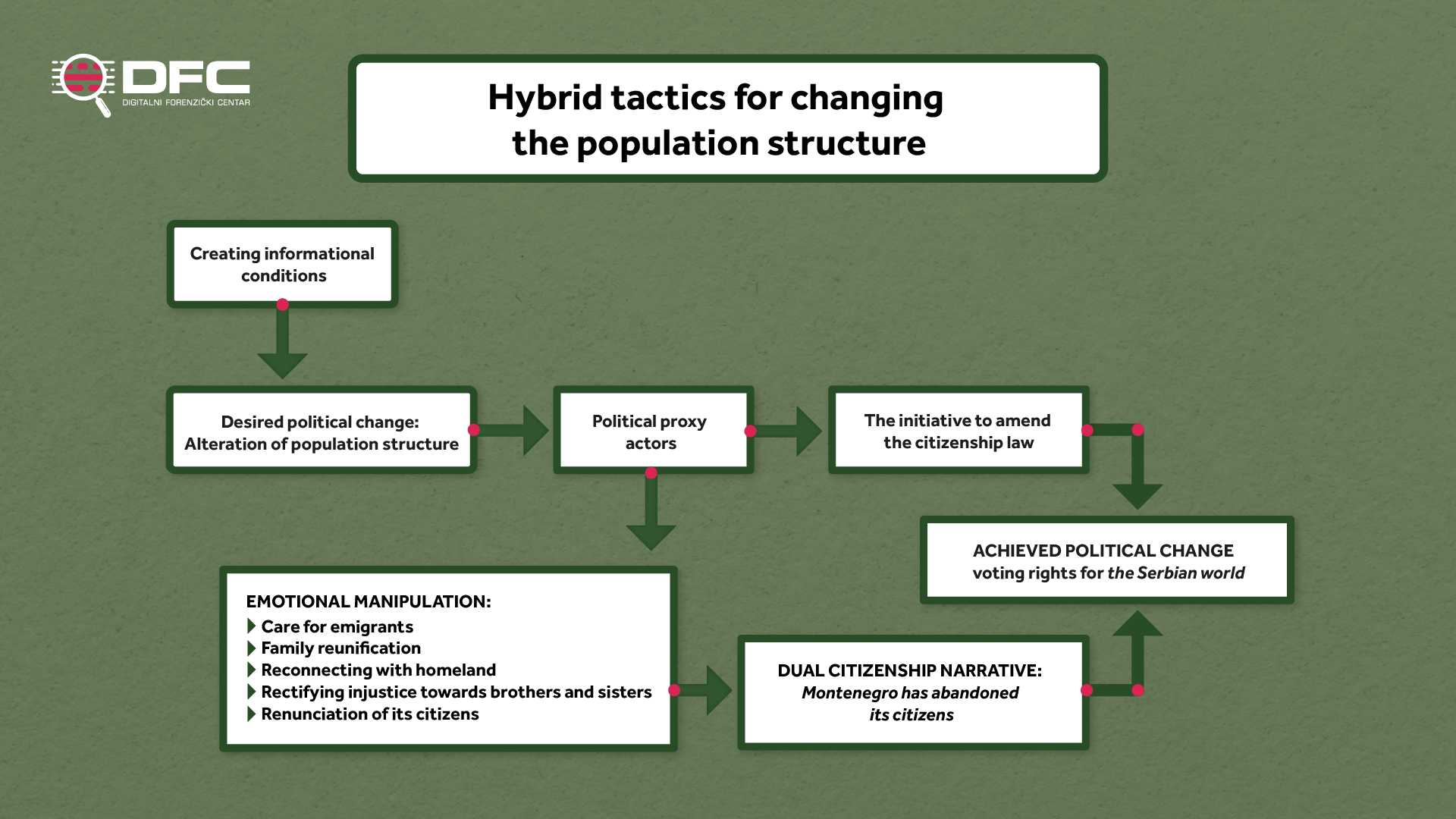

Prioritizing changes to the Law on Montenegrin Citizenship and the potential liberalization of dual citizenship rights represent a clear form of hybrid influence. The serious implications of these changes for Montenegro are being masked by using manipulations and emotional narratives.

It is revealing to see that the campaign for the introduction of dual citizenship and the amendment of the Law on Citizenship intensified especially after the 2023 parliamentary elections, coinciding with the formation of a government that includes proxies of Serbian influence, aligning their policies with those of official Belgrade.

The DFC analysis focuses on deconstructing the manipulative narratives propagated by proponents of the amendments to the Law on Citizenship and the implications these changes may have on Montenegro’s European integration and NATO membership.

Alignment of Policies with the Interests of Belgrade

The issue of amending the Dual Citizenship Law has been brought to the forefront by political actors who form the majority in Montenegro’s 44th Government. Alongside narratives of accelerated EU accession, representatives of the For the Future of Montenegro coalition have increasingly presented the amendments to this law as a basis for so-called reconciliation in Montenegro. The Speaker of the Montenegrin Parliament, Andrija Mandić, and the President of the Democratic People’s Party, Milan Knežević, are the loudest advocates for amending the Montenegrin Citizenship Law. In December 2023, Speaker Andrija Mandić announced steps toward amending the Citizenship Law and the Constitution in the section concerning the official language. In 2021, Zdravko Krivokapić’s government initiated amendments to this law, sparking protests in Montenegro due to fears of demographic engineering. On the eve of a vote of no confidence on February 4, 2022, Krivokapić’s government made a decision allowing the calculation of five years of temporary residence and five years of permanent residence in Montenegro to count toward the ten years required for citizenship. The previous legal requirement stipulated ten years of continuous permanent residence in Montenegro. This regulation remains in effect, while the Constitutional Court has yet to rule on its constitutionality.

The narrative promoted by representatives of the New Serbian Democracy and the Democratic People’s Party consists of two vectors of influence on public opinion. The first vector is based on reconciliation by addressing what they describe as the discriminatory treatment of Serbs in the past. The second vector is framed around the idea that these legal changes would reunite families, allowing those living abroad who are connected to Montenegro by heart and heritage to obtain Montenegrin citizenship. The Speaker of the Parliament employs this emotionally manipulative narrative when discussing the status of Montenegrin emigrants in Turkey. During a visit to Turkey on December 10, 2023, he stated that they would work together on a legal solution to ensure that all those with roots in Montenegro could acquire citizenship as easily and efficiently as possible. It is noteworthy that in his congratulatory message on the Day of the Municipality of Gusinje, Andrija Mandić emphasized that Montenegro will never forget its emigrants and will work to ensure that they become citizens. In August 2024, the leader of the Democratic People’s Party propagated a similar narrative, stating that dual citizenship with Serbia would correct the injustice felt by our brothers and sisters who feel abandoned and forgotten. By merging the hegemonic aspirations of the Serbian regime with ethnonationalism-driven emotional manipulation concerning the reunification of Montenegrins around the world who are connected by blood and family ties, the pro-Serbian proxy network instrumentalizes the issue of dual citizenship to undermine Montenegro’s national sovereignty. It is also significant that before the 2020 parliamentary elections, the For the Future of Montenegro coalition launched an application called Stay Home, through which citizens could report individuals who had a residence in Montenegro but also residence and citizenship in another country. MP Slaven Radunović of the For the Future of Montenegro coalition described this activity as a fight against phantom voters.

Parallel to the activities of Serbian influence actors, Prime Minister Spajić used the phrase in September 2024 that Montenegro must not abandon its children and mentioned that there are around 300,000 cases that the proposed dual citizenship law should recognize. Additionally, reinforcing the narrative about the restrictiveness of the current law, he stated that the amendments to the Citizenship Law would prevent new citizens from voting for the next ten years. It is noteworthy that the Prime Minister is linking voting rights with changes to the citizenship law. However, voting rights in Montenegro are regulated by the Constitution, specifically, Article 45, which states that the right to vote and to be elected is granted to Montenegrin citizens who are 18 years old and have resided in Montenegro for at least two years. This means that any restriction—whether 10 years or otherwise—on the right to vote or be elected for Montenegrin citizens would be unconstitutional.

Security Aspects and the Russian-Serbian Agenda

Projections by independent experts suggest that lifting the ban on dual citizenship could lead to the expansion of Montenegro’s voter register by over 150,000 new voters. The change in voter structure, undermining of state sovereignty, and the de facto erasure of borders with Serbia are justified by pro-Serbian actors through a manipulative emotional narrative that Montenegro is the only country in the world to have abandoned its citizens.

By using this manipulative narrative about a state abandoning its citizens, Serbian proxies devalue any form of debate on such an important issue. Granting Montenegrin citizenship based on heritage from Montenegro would influence ethnic and national tensions within the country and completely halt the agenda of Montenegro’s rapprochement with the EU. On September 4, the European Commission stated that as a candidate country, Montenegro should refrain from any measure that could undermine the country’s strategic path to the EU or the security of the EU, including using prerogatives for granting citizenship.

A polarized Montenegrin society, with potentially several hundred thousand new citizens, would pose a risk to the EU’s foreign and security policy. Additionally, the dual citizenship model would allow the authoritarian regime in Belgrade to shift Montenegro’s pro-Western course without changing borders or the state’s legal status, but rather through controlling the electoral process. If granted voting rights through dual citizenship, the predominantly anti-Western sentiment among Serbian citizens would reflect Montenegro’s strategic pro-Western orientation. According to public opinion polls, 88% of Serbian citizens oppose NATO membership, and only 33% support joining the EU.

Russia and Serbia’s long-term strategy to undermine Western security institutions would be realized through Montenegro as an unreliable NATO member, undermining the Alliance’s strategy in the region and promoting anti-Western and authoritarian narratives.

Pro-Serbian proxies are using the dual citizenship mechanism based on a model Russia attempted to impose on former Eastern Bloc countries after the collapse of the Soviet Union. Serbia’s strategic documents addressing the issue of Serbs in the region, starting with the Law on the Diaspora and Serbs in the Region from 2009 and the Strategy for Preserving and Strengthening Relations between the Home State and the Diaspora, and the Home State and Serbs in the Region from 2011, are conceptually identical to the Kremlin’s strategies regarding Russians in the near abroad.

The Russian Nation strategy, established by Boris Yeltsin’s government, encompasses 25 million Russians living in the near abroad. This figure forms the basis of the strategy for interfering in the internal affairs of neighboring states following the collapse of the Soviet Union, by instrumentalizing the Russian population that remained in the former Eastern bloc. Essentially, the Russian Nation strategy involved granting dual citizenship to Russians living in the Baltics. The three Baltic states – Estonia, Latvia, and Lithuania -rejected such a solution.

With Vladimir Putin’s rise to power in Russia, the issue of Russians in the near abroad was highlighted through the 2013 Foreign Policy Concept of the Russian Federation. This concept entails the protection of Russian minorities by promoting culture and language. Under the guise of protecting identity, language, and culture, Russia began hybrid activities in 2013 that led to the annexation of Crimea.

In 2011, Serbia adopted the Strategy for Preserving and Strengthening Relations Between the Mother Country and the Diaspora and Between the Mother Country and Serbs in the Region. The principles of this strategy provide the groundwork for hybrid activities in the Western Balkans by strengthening institutions and organizations that undermine the constitutional order of regional states, applying the principles of so-called soft power.

The Declaration on Protection of National and Political Rights and the Common Future of the Serbian People, adopted at the All-Serbian Assembly on June 8, 2024, predominantly targets Montenegro through Article 32, under the pretext of protecting Serbian culture, identity, language, and the Cyrillic script. On June 9, 2024, the day after the All-Serbian Assembly, Milan Knežević stated: We want to sign an interstate agreement on dual citizenship, we want special and spiritual ties with Serbia, and to create a foundation so that the Srebrenica Resolution never happens again. Following the model of special ties, Russia and Belarus signed the Union State Treaty in 1999, which outlines the deeper integration of these countries in all socio-political aspects. Additionally, the Russian Federation’s Foreign Policy Concept, in Article 3, paragraph 14, mentions the protection of the interests of Russians in the near abroad through the preservation of the pan-Russian identity

Baltics – Montenegro – Dual Citizenship

The three Baltic states—Estonia, Latvia, and Lithuania—base the restrictiveness of their citizenship laws on the size of their countries and populations, aiming to preserve sovereignty and prevent foreign political and security influence. Estonia, with 1.3 million, and Latvia, with 1.8 million inhabitants, do not allow dual citizenship. They also raise concerns about dual citizenship regarding loyalty to the state in case of potential wartime threats, such as military service. After the collapse of the Soviet Union, these three Baltic states adopted restrictive citizenship laws due to the immediate threat they perceived from neighboring Russia. This strict stance on dual citizenship is part of their effort to maintain territorial integrity and sovereignty after gaining independence in 1991. The justification for such laws became evident after Russia’s annexation of Crimea in 2014, when the Baltic states became targets of Russia’s hybrid activities. By spreading disinformation and using propaganda through outlets like Sputnik and RT, Russia stoked ethnic tensions in the Baltic states and instrumentalized the Russian-speaking minority.

After gaining independence from the Soviet Union in 1991, Estonia and Latvia passed citizenship laws that granted citizenship only to those who held it before the Soviet occupation or their descendants. Russian citizens who migrated during the Soviet era or their descendants, who did not acquire Estonian or Latvian citizenship, are considered non-citizens in these countries. The term non-citizen refers to the specific status of residents in Estonia and Latvia who are not citizens of those countries or any other state. These individuals are predominantly of Russian ethnic origin, and Moscow uses their unresolved civic status as an instrument for hybrid actions against Estonia and Latvia. By spreading disinformation about the alleged violation of the civil rights of non-citizens, i.e., the Russian minority, Russia has heightened ethnic tensions and antagonized the Russian-speaking population in the Baltics through the information space. In 2018, Vladimir Putin called on the EU to halt what he described as the massive violation of human rights being committed against the Russian-speaking minority in Latvia and Estonia.

For decades, the regime in Serbia has antagonized the Serbian national and ethnic population in Montenegro. Analogous to Russia’s hybrid activities toward ethnic Russians in the Baltics, the regime in Belgrade uses identical methods against Montenegro. Through proxy actors, Aleksandar Vučić’s regime seeks to plunge Montenegrin society into a state of permanent instability. Pro-Russian and pro-Serbian structures within the Montenegrin government take advantage of their institutional position, being part of the parliamentary majority, to present their agenda as the desire and aspiration of the majority of the population. Similarly, the pro-Russian proxy government in Georgia used its institutional advantage to pass a law requiring organizations receiving more than 20% of their funding from abroad to register as foreign agents. This led the EU to halt accession negotiations with Georgia, effectively stalling the country’s pro-European agenda.

International Conventions and Court Rulings

Montenegro has the right to apply restrictive provisions in its citizenship laws based on several international conventions that emphasize state sovereignty in determining who qualifies as its citizens. According to the European Convention on Nationality (1997), each state has the right to freely decide on matters of nationality, including the possibility to restrict or prohibit dual citizenship in accordance with domestic law. The convention acknowledges that there are varying approaches to multiple citizenships and allows contracting states to apply their policies regarding the retention or loss of citizenship when their nationals acquire another nationality.

By adopting the Law on the Ratification of the European Convention on Nationality in 2010, Montenegro retains the right to limit dual citizenship and tailor its policies to the specific interests of the country. Additionally, the 1963 Convention on the Reduction of Cases of Multiple Nationality recognizes the right of states to prevent cases of multiple citizenships, particularly when this aligns with their national interests.

On the other hand, the rights guaranteed under Article 3 of Protocol No. 1 of the European Convention on Human Rights (ECHR) entail the obligation of states to hold elections that ensure the free expression of the citizens’ will, which includes individual rights such as the right to vote (active aspect) and the right to stand as a candidate (passive aspect). The rights guaranteed by Article 3 of Protocol No. 1 of the ECHR are not absolute and may be restricted. In a series of cases dating back to 1961, the European Commission found complaints related to voting restrictions based on residency to be clearly unfounded and dismissed them, taking the position that state legislatures have the right to limit the influence of foreign citizens on elections that primarily concern residents.

In relation to current debates about potentially allowing multiple citizenships, the case of Shindler v. the United Kingdom (2013) is noteworthy. This case addressed the voting rights of UK citizens who were non-residents and had lived abroad for more than 15 years. The European Court of Human Rights (ECHR) upheld the UK’s 15-year restriction on expatriates’ voting rights, concluding that this was within the state’s margin of appreciation. This margin allows states a certain degree of discretion in setting policies, especially regarding electoral laws, as long as the restrictions serve a legitimate aim and are proportionate. In this case, the UK argued that long-term non-residents had weakened ties to the state and were less affected by its policies. The ECHR accepted this argument, ruling that the restriction was reasonable and did not violate the right to free elections under Article 3 of Protocol No. 1 of the Convention. The ECHR held that states are not obligated to grant non-residents unlimited access to this right. The fact that some member states allow non-residents to vote does not establish any common approach or consensus on how to resolve this issue. States, in line with their policies and legislative frameworks, have the freedom to assess and choose how to address the matter of non-resident voting rights.

Electoral Manipulations

In the study titled Unbreakable Ties and Geopolitical Strategy – Serbia’s Influence in Montenegro, the Digital Forensic Center (DFC) highlighted how the regime in Serbia manipulates voting rights and engages in electoral engineering in the Western Balkans. During the 2021 local elections in Nikšić (Montenegro), the elections in Bosnia and Herzegovina, and the 2023 Belgrade elections, voters were brought in from other countries to manipulate electoral outcomes in favor of the regime led by Aleksandar Vučić. Using sophisticated tools of hybrid warfare, this regime undermines the integrity of elections across the Western Balkans.

A glaring example of such abuses occurred during the 2023 local elections in Belgrade. The CRTA observer mission documented voter migrations that they estimated had a decisive impact on the election results in Belgrade. CRTA reported that at least 24,000 voters migrated for the elections in Belgrade. They also found evidence suggesting that this practice was used, albeit on a smaller scale, in the previous election cycle in April 2022. This voter migration was facilitated by the abuse of dual citizenship rights, particularly among citizens of Serbia living in neighboring countries, notably Bosnia and Herzegovina. Similar practices were observed during local elections in Srebrenica, Bosnia, in October 2024.

It is reasonable to expect that similar abuses may be applied in Montenegro, given that the ruling political structures are closely aligned with Aleksandar Vučić’s regime. Even without dual citizenship laws, Montenegro already faces significant issues with voters who hold two citizenship or residences, violating Montenegrin law. The Center for Monitoring and Research (CEMI) estimated that around 80,000 voters in Montenegro illegally maintain dual residency, mostly in Montenegro and Serbia or Bosnia and Herzegovina. CEMI reported, a month before the May 2021 elections, that 10.5% of voters in Herceg Novi held both Montenegrin and Serbian or Bosnian citizenships, with some holding all three.

In July 2024, Darko Dragović, a member of the Europe Now Movement, announced plans to liberalize dual citizenship and finalize a bilateral agreement between Montenegro and Serbia regarding voting rights. According to this agreement, voting rights in Montenegro would be granted to citizens who meet a ten-year residency requirement. However, this agreement raises constitutional concerns, as the Montenegrin Constitution requires that voting rights be granted only to Montenegrin citizens with two years of residency in the country. Milan Knežević, leader of the Democratic People’s Party (DNP), stated this proposal on October 10, 2024, suggesting that Serbia would provide Montenegro with residency data for its citizens under this agreement.

In the past, Serbia has refused to cooperate and share data with Montenegrin institutions to rectify irregularities related to residency requirements. The only known instance of Serbia’s Ministry of Internal Affairs (MUP) providing such data occurred during the presidential campaign when, at the request of Montenegro’s State Electoral Commission, they revealed that current Montenegrin Prime Minister Milojko Spajić violated the law by holding both Montenegrin and Serbian citizenships. However, a similar request for Andrija Mandić did not result in any disclosure from Serbian authorities regarding his citizenship or residency status.

Conclusion

Representatives of the Russian-Serbian influence, who are part of the current parliamentary majority in Montenegro, are continuously attempting to shift boundaries and, through an established methodology of gradually acclimatizing Montenegrin society to previously unacceptable views and unimaginable solutions, to implement initiatives that could directly jeopardize the national interests and strategic goals of Montenegro. The initiative to introduce dual citizenship with Serbia is a glaring example of this.

Montenegro has adapted the issue of dual citizenship to regional security and demographic challenges. Changes to the law on dual citizenship tailored to Serbian-Russian proxies would plunge Montenegro into a state of permanent instability, completely marginalizing the agenda for the imminent accession to the EU. Their goal is to significantly narrow the space for rapid EU membership that has opened up for Montenegro. The destabilization that changes to the citizenship law would cause would certainly contribute to losing support for Montenegro to be the next member of the EU, which is currently anticipated from Brussels.

Ultimately, changes to electoral rights would undermine and derogate the integrity of the electoral process, which would be held in an environment of complete control by the regime in Belgrade, regardless of who would be in power in Serbia at that time. Elections in Serbia and Bosnia and Herzegovina (Republic of Srpska) have already clearly shown this. The sensitivity of a system with a small number of voters, such as Montenegro’s, clearly indicates that any change can play a crucial role in gaining power.

The introduction of dual citizenship without comprehensive expert analysis and public discussion involving prominent legal experts and institutions from Montenegro and the EU would certainly jeopardize Montenegrin national interests, sovereignty, and national security, and Montenegro would completely become part of the Serbian world.

A particularly significant issue is how data on dual citizenship and residency would be exchanged between Montenegro and Serbia, given Serbia’s previous practice of generally not providing information on citizenship, with the exception of the case of Spajić. This case is especially indicative regarding the control of state institutions by Vučić’s regime, as well as the clear support of Vučić’s regime for Andrija Mandić during the presidential elections.

According to international conventions, Montenegro retains the right to restrict dual citizenship and to adjust its policy according to the specific interests of the country. Also, although there is currently no specific case regarding voting by individuals with dual citizenship in two countries, Article 3 of Protocol No. 1 of the European Convention on Human Rights protects the right to free elections. However, this article does not obligate states to grant voting rights to all citizens regardless of dual citizenship or residency. States may impose reasonable restrictions, provided they pursue a legitimate aim and do not violate the essence of this right.

The socio-political and security circumstances in the Baltic countries and their relationship with Russia bear some similarities to the situation in Montenegro and its relationship with Serbia. Therefore, Montenegro should follow the example of the Baltic countries regarding dual citizenship policy.

The topic of dual citizenship is absolutely unnecessary for Montenegro at this moment. The focus of Montenegrin political elites should be solely on reforms that will contribute to accelerating the process of European integration and achieving the key strategic goal of Montenegro’s membership in the EU. Raising issues that could halt this path, such as dual citizenship, is not in the interest of Montenegrin citizens and is far from the national interests of the state of Montenegro.